Who is writing SF in India, you ask? Umm, let me tell you a story. A few years ago, as a naïve young writer, I enthusiastically knocked on an ancient door in a busy street of London. I was there to meet a reputed literary agent – a meeting which had been set up by a Booker long-listed author and friend. During the meeting, I introduced my (then) upcoming urban fantasy series, Anantya Tantrist Mysteries – an occult detective who solves supernatural crime in Delhi with a world built on myths and folklores of the subcontinent.

Much to my delight, the reputed gentleman seemed enthusiastic. It changed the moment I mentioned that the series had been published in India. He shook his head. It was impossible, he explained sympathetically, to find a publisher for the series as I did not own “British Commonwealth Rights,” something that all UK-based publishers would demand.

Quick Explainer of ‘British Commonwealth Rights’

To me, as a citizen of an erstwhile colonized land still reeling under the aftereffects of 200 years of slavery, the term “Commonwealth” bordered on the offensive. This was the first time I had heard it used by literary agents and publishers. “British Commonwealth Rights,” in a contract, implies literary rights in 54 English-speaking countries which were erstwhile colonies of the British Empire. Ironically, the forward-thinking, language-conscious publishers who tweet using #OwnVoice and #BlackLivesMatter have not considered removing this clause from their legal contracts that divided the world along colonial lines of the 19th century.

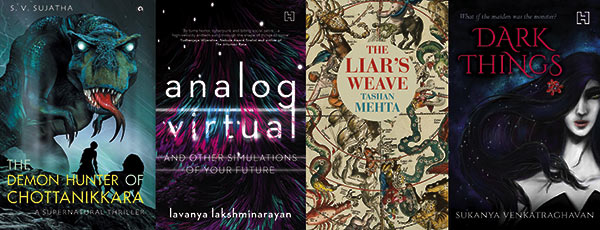

The clause encapsulates the expectation that decision makers in the publishing industry have for genre works that emerge from the East, including India. “Big international publishers reinforce the existence of colonial and orientalist expectations when it comes to Indian writing, particularly when the writer is residing within the subcontinent,” says Lavanya Lakshminarayan, whose debut work Analog/Virtual (2020) got rave reviews in the subcontinent but is still not published in the West.

When Lavanya was shopping her novel, she was asked to write a “sellable” novel which could be the next “Slumdog Millionaire meets American Gods.” She developed the idea into a story, but couldn’t write it. “Why must we prove our ‘Indian-ness’ in colonially acceptable terms first?” she laments. Perhaps that’s why colonialism remains one of the major themes in Indian SF other than exploring an increasingly fractured democracy, gender violence, religious divisiveness and climate emergency through futuristic dystopias.

SF in India has themes of colonialism and climate emergency

“The legacy of colonialism, social and religious cleavages and climate change are the three core themes we find occurring and recurring in contemporary South Asian SFF,” agrees Gautam Bhatia, an editor with Strange Horizons who also debuted a SF novel this year. There is a reason. Most editors and their sales teams in New York and London continue to look for an exotic version of India meant to entertain a colonial, mostly white gaze.

To many debut authors, like Lavanya and Gautam, the odds seem so stacked against an Indian author finding a publisher in the West, that they have stopped trying to find a fit. Gautam did not reach out to agents in the US or UK for his debut novel The Wall, which is a fantastic depiction of a city trapped within its own rigid structures, completely relevant for the Western readers of today. He assumed it was not something the West publishers would connect with. “I was clear in my head that I was writing it as an Indian SFF writer, for an Indian audience,” he says. However, he laments that Varun Thomas Mathew’s The Black Dwarves of the Good Little Bay (2019) – a wonderful novel set in an apocalyptic, post-climate Mumbai where all citizens live enclosed by walls and lost in virtual reality – missed the global publishing boat. Similarly other Indian authors writing, in my opinion, globally relevant fiction, have not desired to spend time to find representation in the West.

The list includes: Nilanjana S Roy who wrote The Wildlings, a literary marvel with a small band of Delhi cats as protagonists; and Manjula Padmanabhan whose The Island of Lost Girls and Escape are important feminist SF works that explore the story of Meiji, the only surviving female in a land where women have been exterminated.

Even Samit Basu, one of the best known genre authors writing in Indian English, who has a robust following in the West, decided to take the self-publishing route rather than wait for a publishing contract for his latest near-future political genre novel, Chosen Spirit (2020) – set in the late 2020s in India, where the protagonist works as a “reality controller” or a professional image-builder in charge of the livestream of politicians. The reason, in Samit’s case, was he could not wait for an agent to shop his book with the publishers in the West, as that would take time. For a near-future novel, releasing in the pandemic year, time was not a currency he had.

Breaking into international markets

Perhaps it’s difficult to embrace something new, feels Tashan Mehta, whose debut The Liar’s Weave (2017) is a literary slipstream through imagined and real Indian history where astrology is real and people’s lives revolve around it. Even though The Liar’s Weave was shopped around in the US, it was rejected as it did not fit into the industry’s “comfort zone making it a destabilizing experience.”

This culturally “destabilizing experience” that people who live in dominant cultures are not that used to is something that Indians grow up with. Like Tashan and me, Indian readers have grown up on a healthy dose of Enid Blyton, without knowing what a “scone” or “marmalade” is. The dominant culture, however, does not come with this experience of reading fiction based in other cultures, making it harder for them to connect with fiction emerging from the blood of other lands.

There are marvelous exceptions to this general experience when it comes to SF in India. The talented Indra Das, whose The Devourers (2015) won the Lambda Literary Award for Best LGBQT Novel, has been able to bound the barrier, developing a readership, a fan base and recognition in the West as much as in India. There are also Indian diaspora and emerging writers who have better visibility as they are based in the US: Mimi Mondal, one of the few Dalit voices writing SF, who won the Locus Award in 2018 for her anthology Luminescent Threads: Connections to Octavia E. Butler and is known for short stories; Nibedita Sen, a Hugo Award, Nebula Award, and Astounding Award-nominated queer writer; Shiv Ramdas, who writes both speculative novels and short stories and has been nominated for a Hugo Award, Nebula Award, and Ignyte Award in the same year. S.B. Divya, who, after establishing herself as a short story writer, debuts with her novel Machinehood in 2021. The list also includes established Indian-American writers like Vandana Singh and Amil Menon.

Most of the Indian authors who could establish themselves in the West started writing in the short story format. Magazines like Strange Horizons, Tor.com, Fireside, Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Podcastle are fissures in the publishing wall, open to new writing and bringing in lived, fresh, experimentative perspectives from the East, that are pushing the boundaries of what genre fiction is.

In India as well, it’s short stories which are helping the SF genre in English grow. In the last two years alone, many SF anthologies have been released in India (most are not available to readers in the West): Magical Women (2019) by editor Sukanya Venkatraghavan, The Gollancz Book of South Asian Science Fiction (2019) edited by Tarun Saint, and Strange Worlds! Strange Times! (2018) edited by Vinayak Varma are a few examples.

SF in India is still a nascent market

However, the market still woefully lacks a community to encourage writers. There are no major cons, grants, awards, or niche magazines, except for one: Mithila Review, which has been struggling for funds even though editor Salik Shah has consistently brought out fantastic stories in the last six years of its existence. The situation makes it more efficient for India-based SF writers to aim for magazines and publishers in North America and UK who have established cons, awards, and grants. This keeps anglophone SF publishing centered in the West, feels Indra. “As a result, we often get defined by a Western POV, as is so often the case with a lot of anglophone cultural output with a global tilt.”

As the pandemic changes our society’s DNA again, experimental spaces in genre SF will constrict further. More indie bookstores, a trend which had an upward curve till early 2020 in India and globally, will down their shutters. Publishers across the world will turn conservative in the wake of limited sales and shrinking markets. Finding new writing will more and more depend on popularity-pandering, narrow-thinking, echo-chamber-pushing bots on digital platforms. However, a sliver of hope remains, coded in the very nature of the SF genre. We all write and read SF to escape, or to see an alternate to our lived reality. Hidden behind our visions of dystopia is optimism and hope.

(This article was first published in Locus magazine, a trade magazine based in the US. To read the complete article, please go here. )

One Reply to “SF in India: Challenges, Debutants and More”

Comments are closed.