There’s a djinn that lives next to the Feroz Shah Kotla cricket stadium in Delhi. His name is Laat Waale Baba (The Pillar Saint) and he’s older than the stadium and older than the British rule. Some whisper he’s even older than the city-fort which was built by Sultan Feroz Shah Tuglaq in 1356, after whom the stadium is named. Laat Waale and his assistants, thousands of other minor djinns, live in the skeletons of the once royal city. And they live royal lives. For they get a heap of letters and coins and prayers and fruits and sweets from worshippers every week.

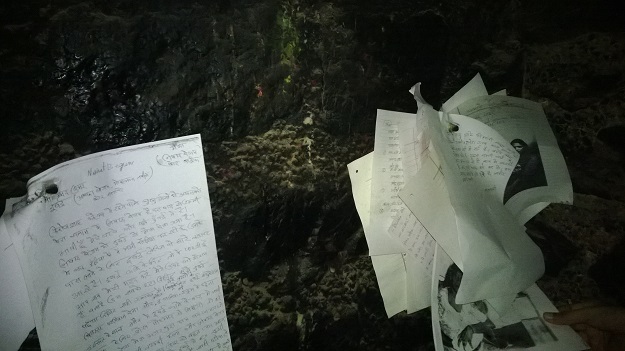

Come Thursday, be it sweltering hot or bone-chilling cold, hundreds of worshippers gather around the Minar-e-Zarreen, a 13.1 meter high, polished sandstone pillar that stands in the middle of the ruins. The pillar, which is believed to be the pathway for the djinn and his minor army, is surrounded by a protecting grill put up by the Archeological Survey of India who maintain the Tuglaq ruins. The worshippers stretch their arms through the grill, futilely to try and touch the pillar, their hands full of letters, photocopies and hope. After the trial to touch, they kiss the grill and tie up these letters, full of prayers. They even bring photocopies and photographs so they can post multiple letters to multiple minor djinns in case one of them is not heard. All letters are full of prayers and pleadings, asking for a wish or hoping the senior djinn or one of the minor ones will help them in matters of the heart, or marriage, of wealth or of health. Some even bring their possessed relatives for exorcism in ruined caverns with bats hanging upside down in the dampness, witnessing the thrashings and shrieks.

A worshipper whispered to me that a hundred years ago, under the British rule, these ruins were haunted by ghosts and pretas and thugs and tantrics and dogs and bats and the Pillar djinn wasn’t a saint. He turned into one post Independence when partition changed the dynamics of the capital city. That’s when, people, maddened by grief of what humans could do to other humans, left with no hope and no other saints or gods, crawled to the ruins, clutching letters of hope. They turned to djinns when they saw the worse in human nature. For they hoped that djinns, who according to Islamic mythology live for centuries and are made of smokeless fire, might know something about life and dignity that humans forget. Continue reading “The djinn-saints of Delhi”