Recently caught the movie Troy again one evening browsing through channel. Iliad, the epic poem by Homer, which is one of the stalwarts of classical literature, has been interpreted and reinterpreted from its original form innumerable times through the centuries which succeeded it. (Download the Samuel Butler translation here or just take a look at Wikipedia). The movie Troy, is not Iliad by any standards, though it celebrates the poetry in motion that is Brad Pitt and works brilliantly as a fantastic-version of Homer’s epic fantasy. If he imagined it, why cant we reimagine it to make it relevant to the modern 21st audience?

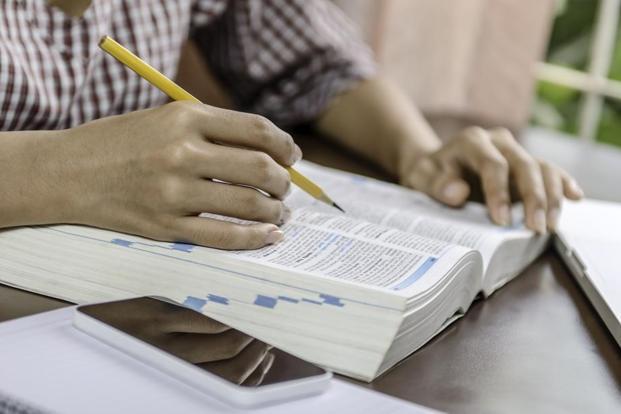

Consecutively, I had also been reading Mahabharata, an old abridged version of English translation by C Rajagopalachari, published in 1978 in a bid to promote indigenous literature in the increasingly West-influenced India, which I was lucky to get my hands on in one of the charming old places in Bangalore. This interpretation is an honoric one which is in awe of the fascinating epic that has been part of our literary heritage. Rajagopalachari sounds almost like a child who’s proud of his parents’ achievement. Fascinating work.

But why I mention both of these incidents here is that both the film and the book reminded me of a two year old assignment on a comparison between the two stalwart epics I had done and quite enjoyed during my MA. Am putting it here in a copy-paste version. Do let me know your thoughts on the same. Oh, and enjoy!

============

THE MAHABHARATA AND THE ILIAD

A comparison between two epic traditions of separate cultures

UNDERSTANDING THE EPIC FORM

Western epic as a genre

The most modern sum up of various definitions of the epic genre in the Western literary circles is that of MH Abrams , who says:

“An epic or heroic poem is applied to a work that meets at least the following criteria: it is a long narrative poem on a great and serious subject, related in an elevated style, and centered on a heroic or quasi-divine figure on whose actions depends the fate of a tribe, a nation, or the human race.”

Abram divides the epics in the Western literary tradition between ‘traditional’ epics or ‘folk’ epics and ‘literary’ or ‘secondary’ epics. Folk epics are the ones which were “shaped by a literary artist from historical and legendary materials which had developed in the oral traditions of his nation during a period of expansion and warfare” (citing examples of the Iliad, Odyssey and Beowulf) while literary epics are composed by “sophisticated craftsmen in deliberate imitation of the traditional form” (citing examples of the Aenied, and Paradise Lost).

Continuing his definition, Abram lists down some essential features that make an epic, which he explains, are derived “from the traditional epics of Homer”. The features, in summary, include:

1. The hero is a figure of great national or even cosmic importance (Achilles in the Iliad)

2. The setting of the poem is ample in scale, and may be worldwide, or even larger

3. The action involves superhuman deeds in battle, such as Achilles’ feats in the Trojan War.

4. In these great actions the gods and other supernatural beings take an interest or an active part. (Olympian gods are all over the place in the Iliad)

5. An epic poem is a ceremonial performance, and is narrated in a ceremonial style which is deliberately distanced from ordinary speech and proportioned to the grandeur and formality of the heroic subject matter and epic architecture.

Abram also looks at the various open-ended definitions by some of the other critics:

“In addition to its strict use, the term epic is often applied to works which differ in many respects form this model, but manifest, suggests critic E.M.W. Tillyard in his study The English Epic and Its Background, the epic spirit in the scale, the scope, and the profound human importance of their subjects; Tillyard suggests these four characteristics of the modern epic: high quality and seriousness, inclusiveness or amplitude, control and exactitude commensurate with exuberance, and an expression of the feelings of a large group of people. Similarly, Brian Wilkie has remarked in Romantic Poets and Epic Tradition, that epics constitute a family, with variable physiognomatic similarities, rather than a strictly definable genre. In this broad sense, Dante’s Divine Comedy and Spencer’s Faerie Queene are often called epics, as are works of prose fiction such as Melville’s Moby Dick, and Tolstoy’s War and Peace; Northrop Frye has described Joyce’s Finnegans Wake as the “chief ironic epic of our time” (Anatomy of Criticism 323). Some critics have even look to the genre of science fiction — in prose and film, like Carl Sagan’s Contact — for the twentieth century’s continuing sense of the epic spirit.”

Epic definition according to the Indian traditions

In spite of what Abram starts out to do when defining the epic genre point-by-point, his definition ends up open-ended. Now, I will speak about another group of critics who define the epic genre according to what they call the “Indian epic traditions”. In a book called the Oral Epics of India (1989) , a group of critics have listed down similar characteristics of the epic tradition according to the Indian oral epics. The essentials are:

1. A narrative which tells a story in song, poetry, rhythmic prose, with perhaps some unsung parts in a poetic, formulaic, ornamental style

2. It is heroic as it tells adventures of extraordinary people—human, quasi-human, semi-divine or divine

3. There are three epic types (in Indian cultures):

• Martial: War, battle, struggle at centre with a focus on the society

• Sacrificial: Heroic act of self-sacrifice or suicide at centre

• Romantic: Individual actions celebrated at centre though threaten group solidarity

4. Deities and humankind: Gods mix in human affairs for their own and the cosmos’ benefit; when trouble threatens, the gods shift it to earth; and epic heroes—and by extension the rest of us—become the gods’ scapegoats. Human suffering is inevitable and life is ruthlessly fatalistic. Important cult deities play active role in events, even if they are not the central characters.

5. Scope: Indian epics are stories full of marvels, but are also more: they present a mythology (or a religion, to believers) and an interpretation of the human condition. Indian oral epics, like the Mahabharata, are often filled with large amounts of didactic material, which works with the narrative to teach lessons, ethical norms, and the collective wisdom of the national or regional culture.

6. Complex intergenerational plots and repeat core character triangles: A core character triangle grouping consisting of a lead hero or heroine and two secondary female or male characters.

7. Protagonist’s character develops through repeated story or plot types.

8. Focus on male protagonists, and present character attitudes (e.g. toward women and human relationships, eg within kinship groups of family or caste) of a male-dominated world.

9. Kinfolk, often the heroes’ close relatives and especially within the same or parallel castes, often pose serious problems and provoke destructive feuds, which drive the epic plot.

10. Themes include dharma (moral law), Fatalism (fate or daiva), Divine grace and the way of bhakti to final release or moksha

In a summary, epics are loosely defined as long verse narratives that tell the heroic stories of one’s tribe. They present the deep questions about courage and moral order, about love and violence, about war and peace which must be answered if a nation is to know itself.

WHERE THE TWAIN SHALL MEET

I will use the above-cited definitions as a starting point to understand the various differences and similarities between the two epics, the Iliad and the Mahabharata.

Through oral traditions

Though attributed to a single authorship, both the Iliad as well as the Mahabharata, were written in Abram’s definition of the ‘primary’ epic. According to Abram, “the epics were shaped by a literary artist from historial and legendary material which has developed in the oral traditions of his/her nation during a period of expansion and warfare.” These epics have been composed without the aid of writing; sung or chanted to a musical accompaniment which means a lot of repeating. Also, since the form is looser, separate stories or episodes from the epic can be detached from the whole and told in completeness. The content of both the epics fit into this definition.

Structure: loose or taut?

The Mahabharata which is claimed by scholars to be a build up of additional stories onto the original writings of Rishi Vyaas from 5th century BC to 4th century AD, has a looser, compiled feeling. The various sections of the book are complete in themselves. Though it is talking about the history of the race of Bharata, there are a lot of detours with separate stories/content in the book which have nothing to do with the story itself. In Anushasana Parva, there’s Bhagavad Gita where Krishna advises and teaches Arjuna and Vishnu Saharanama, which is a long hymn to Vishnu that describes his 1000 names. In Aranyaka Parva, there’s an abbreviated version of the Ramayana as well as the story of Damyanti. The Harivamsa Parva is a compilation of the story of Krishna.

In Iliad on the other hand, though the content is inspired by the stories abounding in Homer’s times, the narrative has a crisper structure. There are lesser detours in the story than the Mahabharata. The poem is compressed with every word made to count in its meaning and understanding, especially in the beginning of the story.

Narrative style

Homer is a third person, omnipotent narrator who is not only retelling the story of the Fall of Troy, but also has access to every character’s mind. The storyteller in that way has control. The style is linear in the sense that the story Homer’s telling has already happened. For example, in Book 12 of the Iliad, Home begins with a flash-forward part the end of the Trojan War.

The narrative in the Mahabharata is complex in comparison. Vyasa himself is both poet and actor in the epic. Vyasa has written the story but Vaisampayana, a disciple of the rishi, is actually telling it. There is a linear form but some open-ended questions like this, make the epic a mystery.

Formal elevated style

Both the epics use an elevated style of language. The Iliad was composed in the Ionic dialect of Ancient Greek, which was spoken on the Aegean islands and in the coastal settlements of Asia Minor, now modern Turkey. The poet chose the Ionic dialect because he felt it to be more appropriate for the high style and grand scope of his work. Similarly the Mahabharata was first written in Sanskrit and then translated into the regional languages.

More than the language, it’s the words, the similes, the epithets for heroes, the archaic, high-style words that make the epics sound like grand works in terms of scope and imagination.

Scope of the poems

The Mahabharata is more than a story about kings, princes, sages and wise men. As Vyasa explains in the beginning:

“What is found here, may be found elsewhere.

What is not found here, will not be found elsewhere.”

It’s a compilation of myths and folks of a culture and its races. There are many deflections and unrelated stories woven into its loose and long structure.

By comparison, the Iliad, takes one aspect of the myth and focuses on just that. The poem is a story of a hero, Achilles, in a fight. Though the scope is elevated in language, the story focuses on Achilles’ development as a character in the few days in the poem.

A lot of divine intervention

In both the epics, divine deities of the culture participate, council, kill and cheat semi-divine humans on Earth. There are many instances in the Mahabharata when the gods come in the heavens to see a fight between two warriors. Gods cheat as well. For example, Indra goes to Karna to ask for his armour so that he cannot win over Arjuna in the fight.

They are mostly shown as merciless, especially if humans don’t follow their wills. Gods even give boons or wreak wrath on humans due to personal differences or in other words, takes sides in the war. In Iliad, Zeus supports the Trojans in the war and even sends Hermes to escort King Priam to Achilles’ camp.

The glory of war

Both the Mahabharata as well as the Iliad seem to celebrate war. Characters emerge as worthy or despicable based on their degree of competence and bravery in battle. In Iliad, Paris, for example, doesn’t like to fight, and correspondingly receives the scorn of both his family and his lover. Achilles, on the other hand, wins eternal glory by explicitly rejecting the option of a long, comfortable, uneventful life at home. The text itself seems to support this means of judging character and extends it even to the gods. The epic holds up warlike deities such as Athena for the reader’s admiration while it makes fun of gods who run from aggression, using the timidity of Aphrodite and Artemis to create a scene of comic relief.

Satya Chaitanya, a scholar in an article ‘Mahabharata – Odes to Red Blood and Savage Death’ lists down various passages from the book where there is glorification of war, the warriors and even bloodshed. Killing according to her in the epic is “a power-game – which in its moments of climax not just thrills, but transports the winner into ecstasies akin to orgasmic moments”. She quotes Duryodhana from the Shalya Parva:

“Fame is all that one should acquire here. That fame can be obtained by battle, and by no other means.”

In another passage from the text:

“The death that a Kshatriya meets with at home is censurable. Death on one’s bed at home is highly sinful. The man who casts away his body…in battle…obtains great glory. He is no man who dies miserably weeping in pain, afflicted by disease and decay, in the midst of crying kinsmen.”

She continues, “These sentences leave no room for any doubt about their attitude towards war. To slaughter the enemy ruthlessly in honorable battle was noble indeed. And to be pierced by a hundred arrows in every limb, to have one’s head chopped off with a single stroke of the enemy’s sword or a well-shot arrow was equally noble.” Take a look at the description of an encounter between Arjuna and Ashwatthama:

“The son of Drona then, O Bharata, pierced Arjuna with a dozen gold-winged arrows of great energy and Vasudeva with ten. Having shown for a short while some regard for the preceptor’s son in that great battle, Vibhatsu (Arjuna) then, smiling the while, stretched his bow Gandiva with force. Soon, however, the mighty car-warrior Savyasachi (Arjuna) made his adversary steed-less and driver-less and car-less, and without putting forth much strength pierced him with three arrows. Staying on that steed-less car, Drona’s son, smiling the while, hurled at the son of Pandu a heavy mallet that looked like a dreadful mace with iron-spikes.”

The realities of war are not ignored, they are instead glorified. The Kshtriya code of conduct is the dharma of the characters in the story. In one of the scenes in Book 9 in the Iliad , Achilles tells Odysseus, Phoenix and Ajax about the two fates he much choose between:

“For my mother Thetis the goddess of silver feet tells me

I carry two sorts of destiny toward the day of my death. Either,

if I stay here and fight beside the city of the Trojans,

my return home is gone, but my glory shall be everlasting;

but if I return home to the beloved land of my fathers,

the excellence of my glory is gone, but there will be a long life

left for me, and my end in death will not come to me quickly.”

In Iliad, men die gruesome deaths; women become slaves and concubines, estranged from their tearful fathers and mothers; a plague breaks out in the Achaean camp and decimates the army. Though Achilles points out that all men, whether brave or cowardly, meet the same death in the end, the poem never asks the reader to question the legitimacy of the ongoing struggle. Homer never implies that the fight constitutes a waste of time or human life. Rather, he portrays each side as having a justifiable reason to fight and depicts warfare as a respectable and even glorious manner of settling the dispute. The word ‘kleos’ meaning ‘the glory earned through battle’ occurs in the epic quite a few times.

Concept of heroism

Heroism then, in both the epics is fearlessness in fighting and standing for what is better for the society, but on the right side. This is the difference between the epic heroes, namely Arjuna and Achilles and the tragic heroes, namely Karna and Hector, in both the epics. Though both Karna and Arjuna follow the kshtriya code of conduct, Karna is killed because he acts wrongly. Just before he is killed, Krishna explains that he insulted Draupadi in the Assembly, so he has no right to ask for a fair fight.

Hector on the other hand, is a tragic figure because he is selflessly fighting for his lands. But he does wrong by flaunting the death of Achilles’ friend Patroclus and making a wrong military decision of keeping most of his army in camps outside the walls of Troy.

But there’s a crucial difference here in between the two epics. Arjuna gains moksha at the end of Mahabharata as he is on the ‘right’ side, but there’s no such release in Homer’s Iliad. Though Achilles does not die in the epic itself, the myth that everyone knows explains that death is impertinent. There’s no escape for any human being from death. Achilles goes the Hector way, albeit a bit later in the battle. Mahabharata then, is more didactic than Iliad in its closures of concepts of ‘evil’ and ‘good’.

Concept of fate

In both the tragic hero’s tales, lies the hand of fate, a very important theme in both the epics. In an instance in the Karna Parva, Dhritarashtra exclaims to Sanjaya, summing up the whole theme of destiny:

“I think destiny is supreme, and exertion fruitless since even Karna, who was like a Sala tree, hath been slain in battle…The fulfillment of Duryodhana’s wishes is even like locomotion to one that is lame, or the gratification of the poor man’s desire, or stray drops of water to one that is thirsty! Planned in one way, our schemes end otherwise. Alas, destiny is all powerful, and time incapable of being transgressed”

Karna is aware of his fate but still embraces it, as it’s his duty. Karna cries to Salya on the day of his death in Karna Parva:

“Who else, O Salya, save myself, would proceed against Phalguna and Vasudeva that are even such?

…Either I will overthrow those two in battle to-day of the two Krishnas will to-day overthrow me.”

He knows it’s impossible to beat the two ‘Krishnas’, but he takes responsibility for the fight as there’s no one else. Everytime, Karna seems to emphasize that he has no choice in the matter and that his hands have been bounded by fate. But Krishna, who’s the ‘right’ voice of the text, brings in the Hindu belief of ‘karma’ when he addresses Karna:

“It is generally seen that they that are mean, when they sink into distress, rail at Providence, but never at their own misdeeds.”

This seems to imply that it’s one’s karma, in other words, one’s choice that decides what’s coming for one. The sway between karma and fate is never really decided in the text.

In Iliad, fate is all encompassing. It is obeyed by both gods and men once it is set, and neither seems able (or willing) to change it. Although the Iliad chronicles a very brief period in a very long war, it remains acutely conscious of the specific ends awaiting each of the people involved. It was considered heroic to accept one’s fate honorably and cowardly to attempt to avoid it. But in a similar case as Mahabharata, fate does not predetermine all human action. Instead, it primarily refers to the outcome or end, such as a man’s life or a city such as Troy. For instance, before killing him, Hector calls Patrocles a fool for trying to conquer him in battle. Patrocles retorts:

“No, deadly destiny, with the son of Leto, has killed me,

and of men it was Euphorbos; you are only my third slayer.

And put away in your heart this other thing that I tell you.

You yourself are not one who shall live long, but now already

death and powerful destiny are standing beside you,

to go down under the hands of Aiakos’ great son, Achilleus”

Here Patrocles alludes to his own fate as well as Hector’s to die at the hands of Achilles. Upon killing Hector, Achilles is fated to die at Troy as well. All of these outcomes are predetermined, and although each character has free will in his actions he knows that eventually his end has already been set. Troy is destined to fall, as Hector explains to his wife in Book 6. Also, Achilles and Hector themselves make references to their own fates—about which they have already been informed. Although its origins are mysterious, fate plays a huge role in the outcome of events in the Iliad. It is the one power that lies even above the gods and shapes the outcome of events more than any other force in the epic. Humans are mere puppets in the hands of gods in the Greek tradition that in Indian where there’s an equal emphasis on choice, or one’s karma.

CONCLUSION

Both the Iliad and the Mahabharata are epic poems as they are all-encompassing in their scope, grand in their vision and tell tales of heroes of a culture and depict the values of the same. In spite of belonging to different cultures, they have one thing in common—they touch the human cord within all of us. Perhaps this is the difference between literature for a generation and literature which inspires many a generations. Iliad and Mahabharata definitely fall into the second category.

Shweta Taneja © 2007