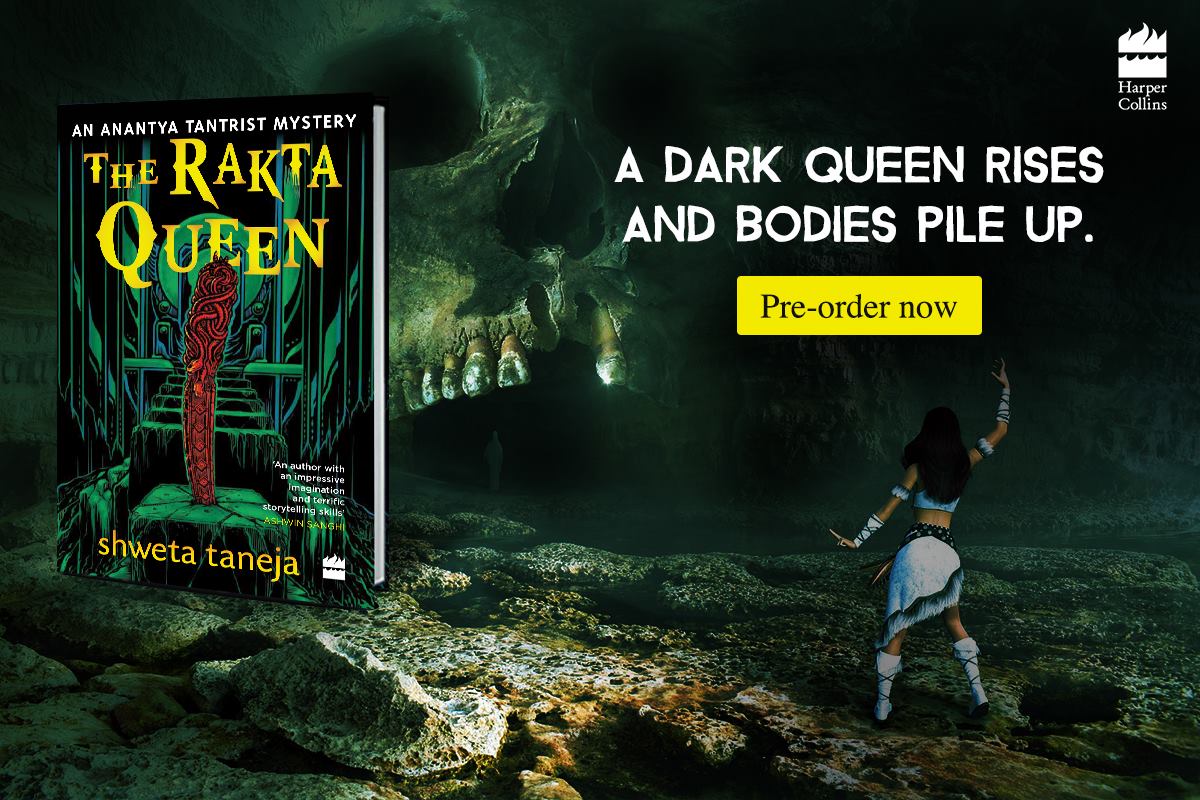

Almost surreptitiously, Indian fantasy has made a niche for itself in the English language in India. Three years ago, when HarperCollins published my urban fantasy novel Cult Of Chaos, An Anantya Tantrist Mystery (2015), I was at the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur. My editor contacted me and requested a video for the upcoming HarperCollins sales conference to explain the genre of the novel.

I dressed up, cycled through the campus and found myself in a professor’s office in the computer science department trying to angle my MacBook to make sure the background was filled with academic books, and not beams. “It’s like Sherlock Holmes solving supernatural crime,” I exclaimed, trying to make eye contact with booksellers through the little black dot on my laptop.

The nightmare for an Indian fantasy author

My aim was to make them avoid the one thing that gives nightmares to every fantasy author: A deep-seated fear that your novel will end up in either the Indian writing or mythology shelves in book stores. This fear has roots in reality: Because for decades, the Fantasy section has been petrificus totalus, with reprints of The Chronicles Of Narnia (1950-56), The Lord Of The Rings (1954-55), the Harry Potter series (1997-2007), A Song Of Ice And Fire (1996-) and, recently, the likes of the Percy Jackson series (2005-) and The Hunger Games (2008-10), with no space for Indian fantasy titles.

Internationally, the urban fantasy subgenre wasn’t an uncharted section. Even the sub-subgenre that Anantya Tantrist mysteries belonged to, that of an occult detective dealing with the supernatural underworld of her city, was thriving enough for some literary agents to actively look for them and for others to discard them because too many of these “occult detective types” had been submitted to them.

Urban human-ish occult detectives with a problematic personal life had invaded subgenres ranging from urban fantasy to paranormal romance. Notable examples included the vampire hunter series Anita Blake by Laurell K. Hamilton (1993-) and The Dresden Files (2000-) by Jim Butcher, told from the point of view of a private investigator and wizard based in Chicago. Indian author Mainak Dhar’s anti-hero zombie hunter in the Alice In Deadland series (2011-12) had also been on shelves for a while.

Continue reading “Indian fantasy has come of age. Here’s why”