(This tribute to John le Carré was first published in The New Indian Express.)

In my pre-teens, I wanted to be James Bond. A daring hero who could save damsels (I saved sexy boys, swooning in my arms) while sipping on martinis in exotic bars of five-star hotels, in handcrafted expensive suits (designer gowns in my case). I imagined myself racing through the alluring world of espionage, delightful deceits and gun-totting, gasping action. I wanted to grab all the glamour with my grubby hands.

Smiley is anti-Bond

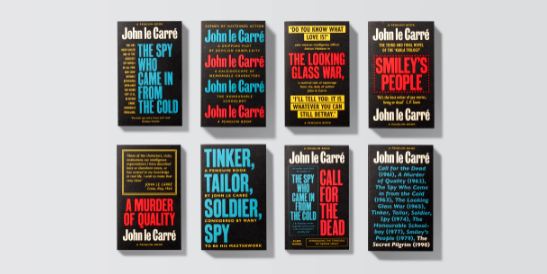

Then I grew up and met George Smiley, an espionage spy like Bond, in John le Carré’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1974). Smiley was anti-Bond. Instead of the swashbuckling suaveness, Smiley paraded reality. He was middle aged, balding, badly dressed, excessively polite, could be bullied, and constantly dealt with a runaway wife. In Call for the Dead (1961), le Carré’s first novel, he was compared to a toad; in A Murder of Quality (1962), he was called a mole.

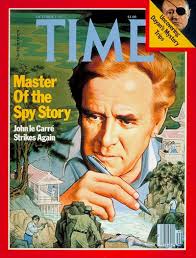

Throughout his career of 25 novels, le Carré — whose real name was David Cornwell and who, unlike armchair writers like this one, worked in the British intelligence before becoming a full-time writer writing espionage — alluded to how the Bondian universe was a fantastical joyride. A modern day fairy tale, with a spy as a hero, cardboard archenemies and damsels in distress.

Le Carré consciously made the characters that inhabited his fictional universe, like Smiley — spies, politicians, damsels, charming liars, villains — a little too real. They were bespeckled bureaucrats who wiped their glasses with their ties, dealt with budget cuts, deceptive spouses and girlfriends and confounding treacheries of their governments, leaving them gutted at morality’s knife edge. The almost satirical Looking Glass War (1965), for example, is plotted around an espionage mission that becomes pointless at the end. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold (1963), which put le Carré in international stardom, portrays methods that its spies employ which are inconsistent with perceived Western values.

A honeycomb of distrust, fragilities and broken people

The writer in me guzzled le Carré’s honeycomb of distrust, human fragilities and broken systems, shaking off the simplistic, glamour-verse of Bond. While developing my tantrik detective series, that two spy worlds inspired my world-building. My protagonist, Anantya Tantrist, was very much a Bondian heroine, trolling Delhi’s streets at night, kicking supernatural threats while swigging somas-on-the-rock; the world she inhabited however was filled with grubby treachery, inspired by the greys le Carré brought into his universes, where friends betrayed and there was no right path, but murky choices, rendering all heroic efforts insufficient.

It’s this constant tension — between the values protagonists stand for, and the murky methods they employ to protect them including deception, violence and betrayal — that manage to shred the same values to scraps of null, and elevate yet another fiction to a deeper reflection on our realityIn our world of disinformation campaigns, ego-boosting echo chambers and fake news, le Carré’s fictional world, like powerful fiction today, slithers underneath our fabricated reality, forcing us to dive into the murky, filthy truth about ourselves and the murky morals in all their grubby glamour.

(This tribute to John le Carré was first published in The New Indian Express.)