I found my first Gond story in a Gond painting exhibition by Indra Gandhi National Centre of the Arts in Bangalore. The series of paintings, in ten by ten feet frames, was a graphic narrative like I’d never seen before. And I was wowed.

It’s Ramayana, I exclaimed, a story I knew, peering to understand the visuals and corroborate it with the story my grandmother had told me ages ago. The story I’d seen again in Ramananda Sagar’s Ramayana TV series which was inspired by the Awadhi text Ramacharitra Manas written by Goswami Tulsidas. However, I couldn’t decipher the visual story. It didn’t collaborate with the Ramayana tale I knew. The one I considered the right one. Curious and fascinated, I contacted IGNCA, started to research on this unusual Gond version, emailed people, called scholars, read books and piece by piece constructed the story that is sung by the bards of Gond, where Ram isn’t the main hero. And so I build up the whole story. Or atleast a version of it. For I’m a storyteller too.

It’s Ramayana, I exclaimed, a story I knew, peering to understand the visuals and corroborate it with the story my grandmother had told me ages ago. The story I’d seen again in Ramananda Sagar’s Ramayana TV series which was inspired by the Awadhi text Ramacharitra Manas written by Goswami Tulsidas. However, I couldn’t decipher the visual story. It didn’t collaborate with the Ramayana tale I knew. The one I considered the right one. Curious and fascinated, I contacted IGNCA, started to research on this unusual Gond version, emailed people, called scholars, read books and piece by piece constructed the story that is sung by the bards of Gond, where Ram isn’t the main hero. And so I build up the whole story. Or atleast a version of it. For I’m a storyteller too.

Have you heard the story where Lakshmana is the real hero in Ramayana? And Ram, that ideal husband and king is but a side character who orders his younger brother to fetch his dice for a game and then blames him for trying to sleep with his wife. I hadn’t.

So I’m going to retell one of the Gond Ramayani tales to you.

Where Sita propositioned Lacchmana

The Gondi tribes worship a local god, Mahadeo, a form of Shiva. The tale goes that one fine day, Ram sits to play dice with Mahadeo and realises that he has left the dice back at his hut. He orders his younger brother Lacchman to get his dice. When Lacchman goes to Ram’s hut, Sita sees him and is attracted to him. “Come and sit in my room for a while,” she says. But Lacchman is a celibate and says no. She bolts the door to hold him. He breaks it open and leaves.

Sita, who is not the chaste wife here as Tulsidas makes her to be, plans revenge. She gives her sixteen maids an off, tears up her saree, throws her jewellery around and sits in the hut, weeping. Ram returns to find his wife in the middle of mayhem with the door broken and her clothes astray. She accuses Lacchman tried of trying to force himself on her. Ram beats Lacchman with a whip, who pleads he’s innocent. To prove it, Lacchman jumps into boiling oil and comes out unscathed. Then he walks through fire, just like Sita did in the better-known version. This time unscathed too. But Ram refuses to believe him. In some versions, he does believe his brother, but decides to leave.

A disappointed Lacchman leaves the village and enters the forest. All the while Sita follows him, sometimes as an old weeping woman, sometimes as a moaning sheep, sometimes as a howling buffalo, asking him to come back. When he doesn’t relent, she curses him that he won’t see any human face for twelve years. The rest of the tale takes him through a dangerous forest, rescuing a princess, facing a serpent monster, a giant elephant and Indra himself. All the while, Mahadeo and even Hanuman helps him.

Meanwhile after Lacchman has left home, his brother and wife fall on hard times. Ram has to take up work as a potter and Sita has to collect fuel from forest. When Lacchman returns home with gold ornaments and a golden body and gifts them his all. Finally he asks everyone to take the name of Ram with the same respect as Mahadeo.

Some tamer versions let Indra’s daughter, Indrakumari, play the role of the woman who blames an innocent Lacchman. But the illicit relationship between a wife and her brother-in-law is quite a common topic in Gondi folk songs. So it might have been Sita. Who knows the truth when it comes to stories and their retellings? This is not the only version which is dramatically different from the Tulasidas version. There are many more. Which one is official? Which one is true? Who knows? As a storyteller, I want to hear what the variations tell me about the people who sing the stories rather than know which story is true. For aren’t all stories tall tales?

Graphic narrative that moves different

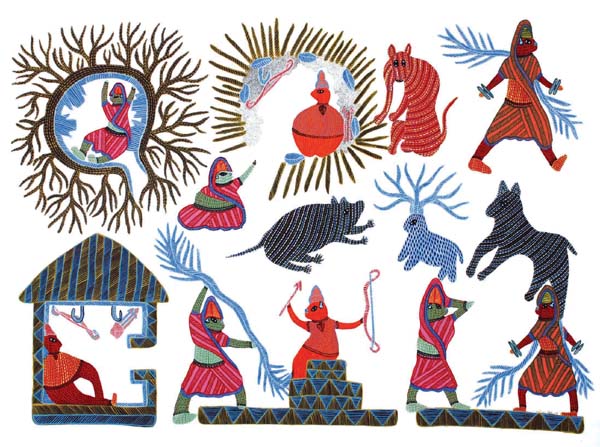

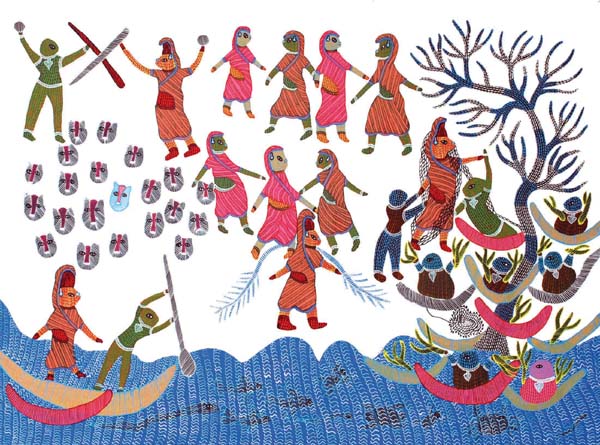

What remains fascinating for me is how images used to tell the story are frameless and wordless. They move from one scene to another, not divided by panels but seamlessly, as the eye would see, without lines, divisions or breaking them into smaller frames. The Gond painting art style, the artwork was figures in 2D, lines and geometric patterns mixing with curves and movement. A lot of movement created in a fabulous mix of vegetable dyes in red, indigo, maroon, pink, yellow, green and brown and blue.

Though some of them came with panels, it remains wordless. I guess because the painting’s used by a storyteller, a professional one or a family member, a grandmother, an uncle, retelling the tales, orally aiding these visual charts of the stories.

You can find more painting samples and the story on the IGNCA site. I am also thankful to the TalkingMyths website for giving me a few parts of this story.

A good write up and thanks for introducing the fans regarding gond arts .

thanks Deepan! There are a few graphic novels and comics which have come with gond artwork. Do try them out. Navayana press has a couple.